Bowie’s portable Japan

By Nick Currie

Special to The Japan Times

I first learned that David Bowie had died while riding the Beetle jetfoil ferry from South Korea to Japan. Among the myriad thoughts that flooded through my mind during the crossing — for Bowie has been my lodestar, an absolutely determinant influence in my life as the musician Momus — was the bittersweet idea that I was returning to a land that provided a large part of Bowie’s inspiration.

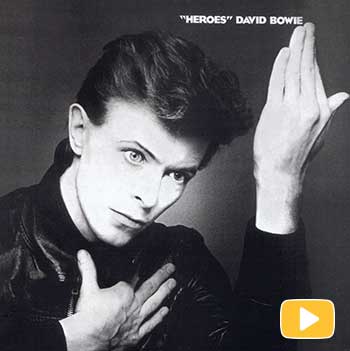

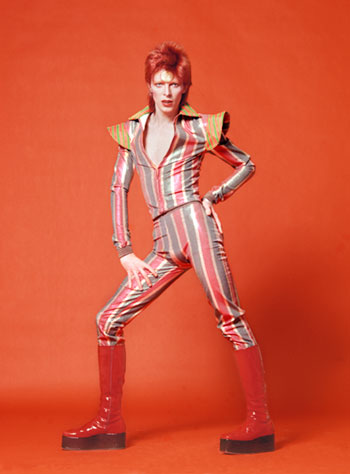

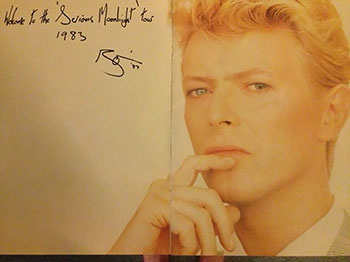

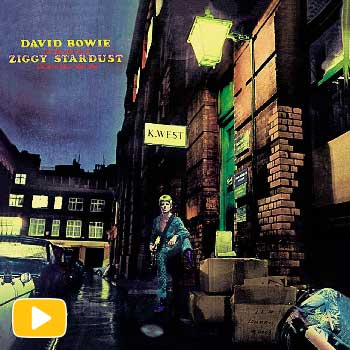

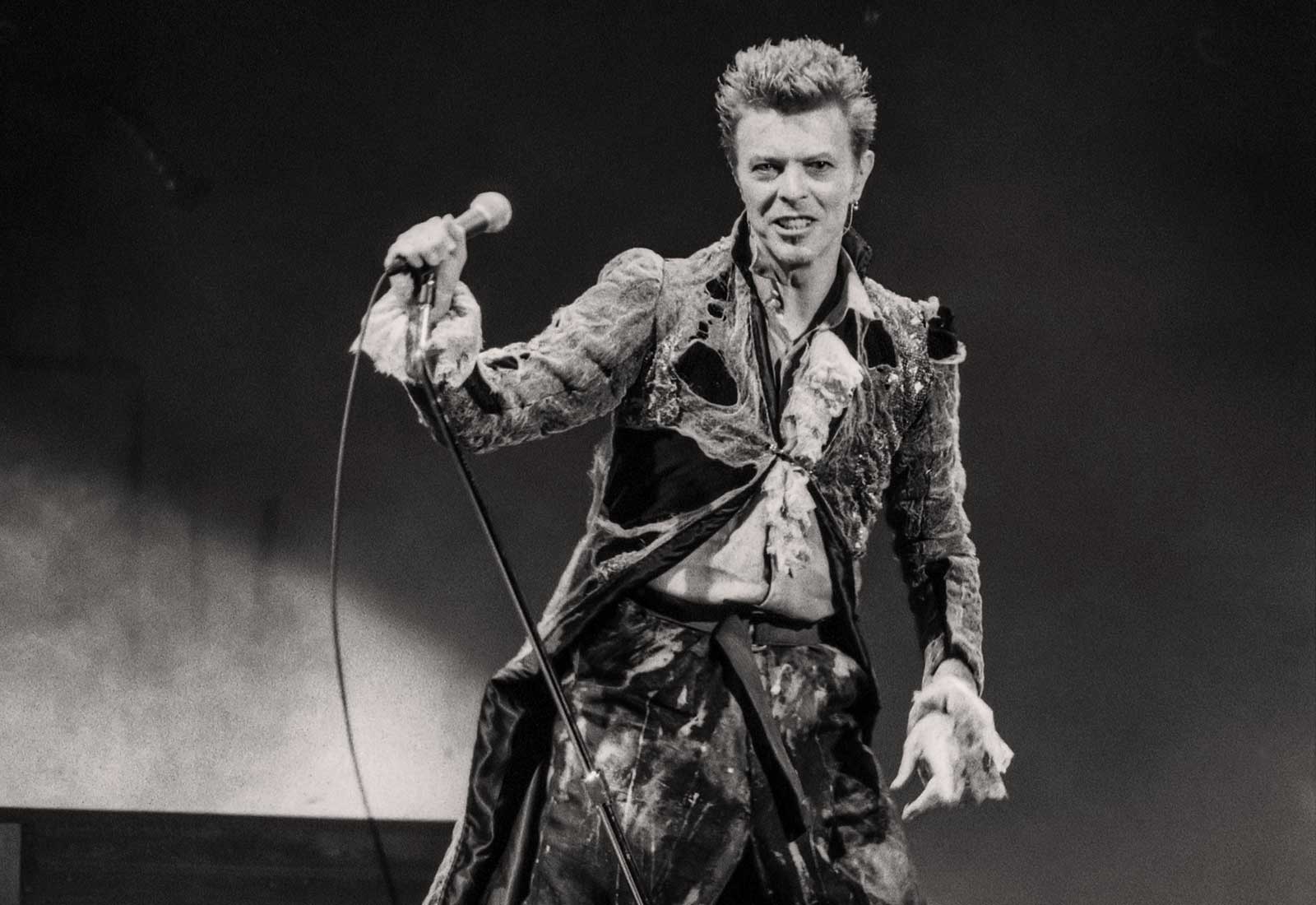

Visions of “Bowie’s Japan” rose in memory as the Kyushu coastline loomed closer. I pictured images taken by photographer Masayoshi Sukita, of course, including the glazed Expressionist-inspired pose on the cover of “Heroes,” later revived for his penultimate album “The Next Day.” I then recalled the costumes of Kansai Yamamoto, in particular an outfit depicting moon-dwelling woodland creatures first unveiled at a 1972 “Ziggy Stardust” show. And I remembered Bowie sipping milk during a 1978 interview for TV show “Star Sen Ichiya” while he explained that kabuki theater had taught him “the discipline of movement.”

I thought of the places in Kyoto — Bowie’s favorite city in Japan — he loved to return to: Tawaraya Ryokan, where he stayed with Iman on their honeymoon, and the now-vanished Cafe David on Sanjo-dori, just opposite the Museum of Kyoto. The “David” in that case was U.S. Sinologist David Kidd (who also died of cancer at the age of 69, back in 1996). Kidd had a house in Kyoto called Togendo, as well as a school dedicated to teaching traditional Japanese arts. Bowie stayed at Togendo in 1979 for some weeks, and even hinted to Western press that the city might become his permanent home.

“I’m not quite sure where to go next,” he told radio interviewer Andy Peebles in 1980. “The East beckons me — Japan — but I’m a bit worried that I’ll get too Zen there and my writing will dry up.”

Sukita took the opportunity of Bowie’s stay in Kyoto to photograph him on the subway — images in which Bowie looks both otherworldly and strangely at home (his fellow Japanese passengers share his lean look and high cheekbones). The photographer also made a series of studio shots in which Bowie, dressed as a salaryman in a belted Burberry coat and makeup redolent of early Yellow Magic Orchestra, stands between the numerals of a huge white clock face, an attache case and newspaper tucked under his arm. The shots didn’t see the light of day until Sukita published “Speed of Life” in 2012, a limited edition book of his Bowie portraits.

In the end, Bowie decamped to New York, which became the closest thing to a permanent home this nomadic soul would have. But whenever I re-enter Japan, I think of myself as somehow inhabiting one of the singer’s discarded skins, living out for him one of the lives he sketched for himself and — ever impatient for the next thing — moved on from. Based on my experience, I would guess that living in Japan wouldn’t have made Bowie’s writing dry up at all — quite the contrary. Japan seems to turn expat artists usefully in on themselves, making their earliest and deepest influences clearer to them and threshing inconsequential chaff from the cultural wheat. As Donald Richie noted in his journal one year into the nearly 70 he would spend in Japan, “Another country, I am discovering, is another self.”

However, Bowie was never short of other selves to explore, and seems to have carried his own personal Japan with him wherever he went. Returning here without him is heartbreaking but it’s also, in a sense, returning to him — to some of this amazing artist’s deepest creative roots.

Nick Currie is a Scottish-born writer and musician who records under the name Momus and currently lives in Kyoto.